Super Slow

By Brad Wieners -

Outside Online

For a stretch, it appeared

as though slow-motion strength training—better known simply as Super

Slow—would take its place alongside the fleeting exercise fads of

yesteryear (OK, it was only two years ago—but it seems like forever). The

claims sounded outrageous: Spend just 20 to 30 minutes, twice a week, doing

traditional lifts at the speed of continental drift, and you'll build strength

50 percent faster than you would with conventional resistance training, kick

your metabolism into high gear, reduce body fat, and raise your levels of HDL

(the good cholesterol). When the hype over Super Slow quickly died down to a

murmur—for reasons to be explained—people soon glommed on to the Next

Big Thing (wobble boards, anyone?).

But it turns out that a handful of

curious athletes and researchers stuck with Super Slow's program and, facing

incredulity from their peers, now swear by its effectiveness.

My own cynicism remained intact until I

began trying to crash into shape for an upcoming kayak expedition that, if I

hadn't been ready for it, could have become a lesson in boat-bound misery.

Fortunately, I ran into Renjit Varghese, 32, a largely self-taught exercise

trainer and owner of Time Labs, a new five-story downtown Manhattan facility

devoted to slow lifting. Born in Kerala, India, and raised outside Cincinnati,

Varghese has been slow-training former pro athletes and business professionals

for six years. Varghese contends that slow training is superior to

multiple-set, clean-and-jerk approaches because (1) it eliminates the ballistic

movements that cause many weight-room injuries; (2) strength improvements come

faster; (3) you spend far less time in the gym, leaving more time for your

sport; and (4) it's more preciseyou keep a record not of the number of reps,

but of the exact amount of time your muscles are stressed, known as "time under

load," or TUL.

After following Varghese's program for six months, I

realized that at least some of Super Slow's claims are legit: I shed ten pounds

and toned up my legs, chest, and arms. During my ten-day kayak trip above the

Arctic Circle in Norway, I found I could pull through the chop for hours at a

stretch. My body recovered faster between paddling days, and I even had better

control of my breathinga welcome asset when I came close to panicking in rough,

freezing seas.

The idea for Super Slow came in 1982, when Ken Hutchins,

a 50-year-old entrepreneur from Conroe, Texas, pioneered the technique after

conducting a study at the University of Florida Medical School. Armed with $3.5

million from the Nautilus Corporation, Hutchins sought to devise a

weight-training regimen that increased the bone density of retirement-age women

who had osteoporosis by building their muscles and improving their circulation

without harming their joints. On a hunch, Hutchins had the women lift

relatively heavy weights very slowly over extended periods. It worked. Some of

the women in the study actually dispensed with their walkers and took up

ballroom dancing again.

Convinced he'd hit on a breakthrough program

suitable for all ages, Hutchins published a 1989 how-to manual, Super Slow:

The Ultimate Exercise Protocol, and began building his own custom exercise

equipment.

The word spread, and by the dawn of the 21st century

athletes of all types (and fitness trend-watchers) had embraced the idea. At

the elite level, 20-year-old professional trials biker Jeremy VanSchoonhoven

took up slow training during last year's off-season. After three months of

slo-mo lifting, VanSchoonhoven had put on seven pounds of lean muscle. "This

sounds ridiculous, but my whole workout is only about 15 minutes long, once a

week," he says. "But now I can compete longer at a top level, and I make fewer

mistakes late in competitions." His increased strength helped him place 16ththe

highest finish ever for an Americanat this year's UCI World Championships.

Last summer, Jason Watson, 30, a Washington State Patrol SWAT team

member, took home seven swimming medals from the Can-Am Police-Fire Games after

slow training, sometimes only once a week, under Greg Anderson of Seattle's

Ideal Exercise. While such results are tempting, beginners should take note:

This efficiency involves a sadistic level of intensity. At first, Watson had to

pop a Tums before each workout just to keep from puking.

Super Slow is

not without its critics. "I don't like it," says fitness consultant and

six-time Ironman champ Dave Scott. "Especially if you're an endurance athlete.

Imagine you're this lean runner strained under this huge, unnecessary load. You

come to the gym, you're already fatigued, and now you have to drop your weights

20 pounds to do just one rep: How do you stay motivated? It can be

psychologically destructive."

Wary of the opinions expressed by road

warriors like Scott, I nevertheless signed up to be trained by Varghese,

following Ken Hutchins's original protocols. According to Hutchins, each

exercise should be 10/5 per repthat is, ten seconds on the positive

contraction, or push, and five on the return, or negative contraction. (By

contrast, a typical rep might be 1/1, 2/4, or 4/4.)

During my workouts,

I do exactly one set of as many reps as I can until my muscles fail completely.

At the end of each rep, Varghese tells me to make the transition from easing

the load down to pushing it back up imperceptibly. Any faster and I'm using

momentum to cheat. All along, Varghese reminds me to take controlled, quick

breaths: "Pant like a sprinter." Holding my breath, he tells me, will just make

me dizzy. At the end of the set, my muscles feel torched by a fresh, white-hot

rush of lactic acid.

Because of slow lifting's difficultyone Super

Slow chest press can be harder than ten quick onesthe program suffers a high

rate of attritionanother reason it's no longer the fitness flavor of the

moment. Wayne Westcott, fitness research director at the South Shore YMCA in

Quincy, Massachusetts, has conducted two studies on slow lifting. The results,

published in the June 2001 Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical

Fitness, indicated that, yes, single-set slow lifters realized a 50 percent

greater increase in strength over eight to ten weeks than did those lifting

weights at a faster pace. However, only two of Westcott's 147 test subjects

opted to continue the slow-lifting regimen.

"The psychological aspect

is just as important for a successful fitness program, and this was just too

tough," says Westcott, who adds that slow lifting is perhaps best applied as a

plateau buster. "Do it for six weeks. But then return to what you're more

comfortable with week in and week out."

Positive testimonials and my

success with slow lifting aside, Westcott and Scott do have a point. The happy

medium may be to see it not as strength training's silver bullet, but rather as

a valuable addition to your arsenal of fitness techniques. Periodically fold it

into your existing routine (see "The Slow-Motion Workout," below) and you'll

soon reap the performance rewards. "There's this kind of undercurrent in Super

Slow circles that almost makes us sound antisports," says Ideal Exercise's

Anderson. "But the point of its high intensity is to give you more time to

play, and better results when you do."

The Slow-Motion

Workout

Use this six week slow-training program to

bust out of a midseason plateau, or as a ten-minute preseason strategy for

building strength and stamina. To get started, grab a stopwatch, find a gym

with strength training machines for the exercises listed below (free weights

are too dangerous), and enlist a partner to clock you. For each exercise,

record the amount of weight used and your time under load (TUL)the elapsed time

from when you start the exercise to when you can no longer continue. When

choosing a weight for each exercise for the first time, select an amount that

allows you to reach muscle failure in no less than two minutes.

Start

by breathing deeply and engaging the weight so it barely starts to move. Now

complete the positive phase of the movement over five to ten seconds, until

your joints nearly lock out. Pause momentarily at the upper turnaround and then

reverse direction, taking five to ten seconds to lower the weight. At the lower

turnaround, slow down further, so that the weight hardly touches the stack, and

then start the next repetition. Focus on moving gracefully, not forcefully,

continuing until it becomes impossible to move the load. When, after time, TUL

reaches two minutes, increase the load by 10 percent.

Give yourself a

minimum of 48 hours' rest between workouts. And it's a good idea to lay off

slow strength training a week or two prior to a major competition. At the same

time, wait 48 hours after an all-day ride or backcountry ski, and up to seven

days after a triathlon, before resuming Super Slow training.

Be sure to

breathe continuously throughout the set with controlled breaths. "Every one of

our clients has said that learning to breathe throughout the exercises has

helped them remain calm and strong under pressure," says Varghese.

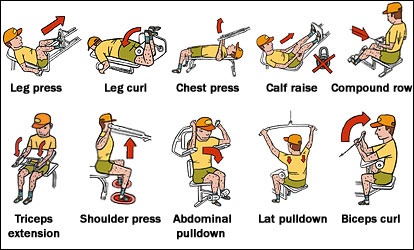

BEGINNER ROUTINE

(First Two

Weeks)

TUL goal: 2 minutes per exercise Frequency: 2 times/week

Leg press

Leg curl

Chest press

Lat pulldown

Abdominal

machine

THE ROUTINE

(Weeks Three to Six)

TUL goal: 2 minutes per exercise

Frequency:

2 times/week

off-season: 3 times/week

Alternate A and B routines on

successive days

A. Leg

press

Chest press

Shoulder press

Triceps extension

B. Leg curl

Calf raise

Lat

pulldown

Compound row

Biceps curl |

(for more workouts see

www.timelabs.us) |